Edward James 'Ted' Johnson

Ted Johnson, the first professional at Moreton Morrell, was born in 1879 and was a true descendant of the old breed of professional who served the game faithfully all their lives, handing down their skill and knowledge from father to son. Ted served Moreton Morrell for sixty-five years, dying in June 1970, at the age of ninety-one. In his youth, he played against most of the finest of the game- "Punch" Fairs, "Fred" Covey, Peter Latham, Lord Aberdare and Edgar Baerlein.

Ted represented an age of tennis players long past- the golden age, as he always maintained. When he spoke of "playing before his Royal Highness at Prince's Club," he was referring to King Edward the Seventh and of a tennis court no longer in existence.

His father, a professional of the old school, had served the first Lord Wimborne for fifty years in the Court at Canford and he brought up his sons the hard way. There were times when the boys would have preferred to have been out in the sunshine rather than practising relentlessly in an indoor court.

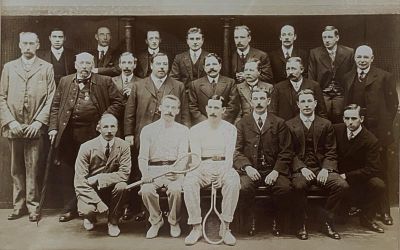

Ted's early posts were first at Princes Club and then at the Tennis and Rackets Club at Tuxedo in the U.S.A. but at the age of twenty-five, he was grateful to return home to become the professional at Moreton Morrell for Charles Garland, an American who may have first met and been impressed by Ted in America. [Image: Johnson (right) 1909 world Championship with 'Punch' Fairs]

Ted had a wide store of reminiscences whether concerned with the characters of his day or with battles fought long ago between the leading professionals and amateurs of the time. In 1909, he contested the World Championship at Brighton, losing by the narrowest of margins to the famous "Punch" Fairs. At a later date he challenged "Fred" Covey for this honour, but the challenge was not taken up and Ted was authorised to claim the title by default, but, typical of the man, he refused to accept an honour for which he had not fought. The Great War intervened and Ted's hopes of winning the coveted prize were never to be realised.

Only a few people can still bear witness to the purity of Ted’s style and to the strength and skill of his game and to the famous underhand twist service which he claimed had the same effect as the then new-fangled American railroad service, for which Ted had little respect and refused to teach.

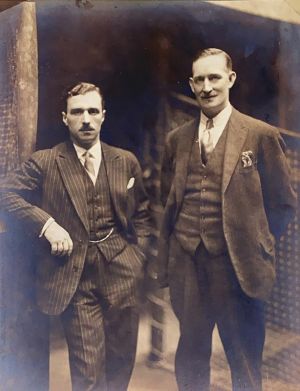

Ted was a very fine coach and coached and worked with Pierre Etchebaster who was World Champion from 1928 to 1952. (Etchebaster's name can be seen in the court fee book.) A story from Newmarket has it that King Edward the Seventh once got so caught up with a match in which Ted was playing that he missed the first race. "Chases for Races” was Ted's laconic comment. [Image: Ted (right) with Pierre Etchebaster]

Extracts about Ted Johnson from The Field, January 18th 1913:

"No professional is more popular, and deservedly so, than Johnson, who is one of the great players of the day, and at the moment has a challenge out for the championship. He is the eldest son of Edward Johnson, now professional to Lord Wimborne at Canford, formerly at Lords and Hampton Court. He was born in London on Feb.20th, 1879, and received his first instructions in the game with his father. At the age of sixteen, he was engaged at the Prince's Club, when the foundation of his game so ably laid before was developed, and he soon showed himself a coming player. He began early to get matches with the leading players, and in 1909, at the age of thirty he challenged Fairs, who was then holder for the championship. The match was played in Brighton in June of that year, and although Johnson was beaten comparatively easily by 7 sets to 2, it was obvious he was a player of the highest class and that it was lack of experience in championship match play that prevented him from doing better, but since then he has decidedly improved.

Tall and splendidly built, Johnson is a fine figure of an athlete. Muscularly he is exceptionally strong, and this is one of the advantages for Tennis, provided it in no way hampers quickness of movement; height, however, has its drawbacks as well as its advantages. It is a gain in so far that it gives extra reach. but there is no question that it is more fatiguing for a tall man to get properly down to the ball than for a man of shorter and more stocky make, and this stooping tells its tale toward the end of a long match or in playing hard games two games running.

As a whole, Johnson, in my opinion, is the most attractive stylist of the very modern form of professional tennis. His stroke is well played without a long swing of the racket, but he gets down well to the ball, cuts the ball heavily, and then it just skims the net, and generally is played with the best of length and direction.

The very pace Johnson sets, and the amount he takes out of himself sometime mean that he gets tired at the end of a hard day's play, and certainly one has noticed that his stroke suddenly seems to lose its fire, and his game its vim, but at its best, when going at top speed, there is no one I would rather see in the court. A most courteous and generous opponent always doing his best whatever the opposition, there is no professional who has deserved his success more."

All who hew Ted speak of his great gift of friendship, of his modesty, and of his staunch sense of fair play. When in the marker's box, his word was law, and woe to anybody who fished for compliments after the game! Almost to the end of his days Ted continued to train new members, throwing the ball after ball onto the penthouse and making the court reverberate with well timed cries of NOW! Despite his age, he continued to give his all to the game. On a bitter cold day he would insist on marking - a dangerous occupation for one of his years. What did it matter if those keen old eyes were sometimes a little inaccurate in spotting the exact chase? The set of balls would be brushed and spotless, the court and penthouse meticulously swept and clean and the rackets taut and ready: an example to all professionals.

Sir Richard Hamilton

The World Championship Dispute

In 1912 and 1913, real tennis made headlines in major newspapers and their letter columns over Ted Johnson's abortive World Championship Challenge, In May 1912, after Fred Covey had defeated "Punch" Fairs, Ted challenged Covey for the Championship and on 31st December, Charles Garland lodged an official challenge with the Tennis, Rackets and Fives Association. To confirm it, he sent a cheque for £50 to the Editor of The Sportsman.

Throughout the period, Covey and his sponsor, the Hon. Neville Lytton were reluctant to take up the challenge, stating that Johnson was not good enough to do so, preferring a re-match with Fairs.

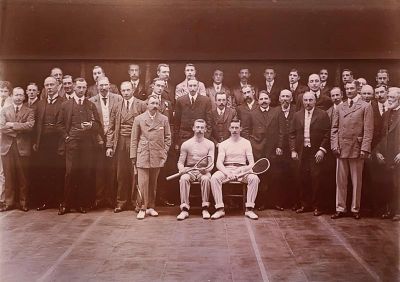

Covey claimed in early 1913 that his practice partner championship was injured and that with his other professional duties he would be unable to play Johnson. He also provided a doctor's certificate which stated that he was incapacitated by varicose veins and would definitely be unable to compete until October at the earliest. Coveys objections raised the question in the real tennis world as to whether a champion was entitled to a championship if not in a fit state to defend it. It was at this stage that the recently founded Tennis, Rackets and Fives Association decided to take full responsibility for the Challenge and ordained that ”unless Covey is willing to defend his title under the Rules of the Association within 21 days after May 4th 1913, Johnson shall be entitled to claim the championship”. [Image: A Tennis match at Petworth October 4th 1911 features 'Punch" Fairs and Ted Johnson playing and Peter Latham and Fred Covey seated next to them on the bench.]

Lytton, a member of the Committee, considered strongly that the Association did not have a remit to settle disputes between professionals. In a letter to The Field he maintained that the World Championship was not in the gift of the TRFA to award, that the Committee was dominated by racquet players who "hardly know one side of a court from another," and that Johnson had yet to beat Covey in a level match. Nor did he believe that the TRFA had approval of the tennis professionals as an arbitrating body. He felt so strongly about the whole affair that he resigned from the Association and encouraged others to threaten to do likewise.

Lytton was an important figure in the game, a fine performer and Amateur Singles Champion in 1911 and 1913. A prominent member of the TRFA, his views and arguments were more likely to hold sway than those of Percy Ashworth who had been deputed by Charles Garland in his absence abroad, to organize and progress Ted Johnson's title challenge.

Johnson must have felt that his chances of a title challenge stood little chance of success and abandoned his attempts but declined to accept the title without having played for it.